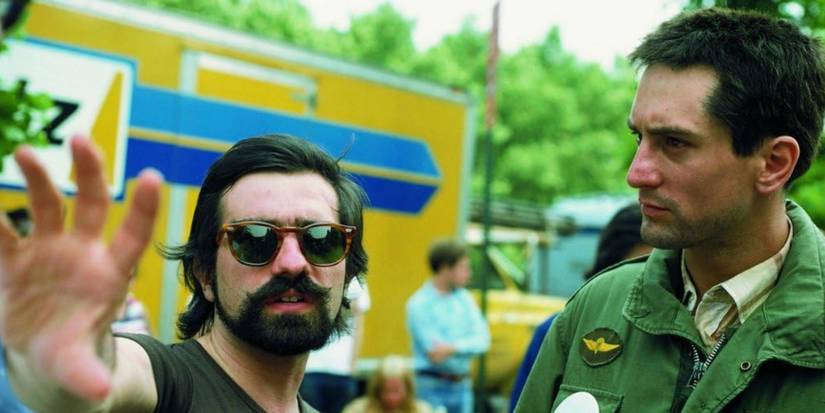

It’s no big secret that the film industry ain’t what it used to be, both in terms of fan appeal and cultural influence, let alone the box office. Turns out you don’t need a crystal ball to see the future. Back in 1997, directors Martin Scorsese and Francis Ford Coppola sat down to discuss the state of the movie business and future dangers facing filmmakers with Geoffrey Gilmore, host of Hollywood Insiders, holding little back when it came to trashing studio leadership. Hollywood didn’t learn a thing. Most of their observations and predictions have proven spot on, from increasingly-inflating exec salaries to the dangers of digital effects, generic movie art, audiences’ shrinking attention spans, and lack of cinematic literacy (anticipating “brainrot” two decades before TikTok made it a pandemic).

20 years at the forefront of the industry afforded them an inside peek at how the proverbial sausage is made, having experienced all the ups and downs, dealing with big-time studios and indie financiers alike. It’s hard to watch it now and not recognize that they both had lost their faith in the people running Hollywood. And for good reason. They were about 30 years off, but they were right when they announced that change is inevitable.

The Head Always Rots First

One of the major changes in moviemaking from the ’70s to the ’90s was the diminishing power of the director. All that power seized by producers and executives, who were beholden to shareholders, not aesthetic sensibilities or storycraft. “When there’s more money to be made, less risk has to be taken,” Scorsese dryly noted. The unprecedented exec salary increase was incommensurate with the studio’s actual stock value then, and so it remains now. Just this year, former CEO Bob Bakish, the man who shepherded Paramount into a headlong descent into the financial toilet, was awarded a totally unwarranted $70 million severance package, per The Hollywood Reporter. Coppola called it, explaining to Gilmore:

“I personally think that the management of the traditional studios are desperate because they know they are unnecessary, they know they’re overpaid, and they know the truth that the films really cost more than they’re publicly admitting, and they’re doing less. So it’s going to change.”

No one took heed of the warning. Execs are still overcompensated, and they still lie about film budgets to mitigate public ridicule in case a film flops hard. The panic to avoid risk and to appease stockholders leads to fewer gambles being taken by hordes of middle managers, nitpicking and micromanaging every film despite having no credentials whatsoever. Somehow, in 30 years, the ridiculous state of affairs Scorsese and Coppola laid out got worse. Today, we see algorithms dictating creative decisions; Cary Fukunaga admitting to GQ in 2018 that he’d grudgingly become accustomed to being bossed around by Netflix’s server bank of data-crunching robots.

“Even the actors’ faces look the same!”

Those familiar with the Fantastic Four fiasco of 2015 might recall the Josh Trank incident. 20th Century Fox tossed money at the young filmmaker only to sabotage and discard him, a phenomenon Coppola and Scorsese warned of. Both directors understood the stakes. In the course of the sit-down, Coppola grimly hints at his future films, insisting that the studios were holding him and his family’s livelihood “hostage,” forcing him to make films he didn’t believe in instead of financing his unnamed, epic “dream project” (most likely he is referring to the 2024 film Megalopolis).

Scorsese took a broader approach, more upset about the loss of personality in movies than any thwarted passion project. “Every poster looks exactly the same,” Scorsese excoriated the dull design of contemporary movie posters. “Even the actors’ faces look the same!” Here’s an article from The Wrap, which illustrates what the Goodfellas director is referring to, just in case you don’t hoard movie memorabilia. Scorsese was right again.

While Scorsese has made some very arrogant statements about what constitutes proper filmmaking and what does not, he speaks from the position of a man who has devoted his entire life to the art form. Irrespective of how you feel about the Marvel franchise, he’s not wrong when he foreshadowed the loss of the traditional cinema-going experience and expectations. Even all the way back in the ’90s, he observed that the younger audience’s “frame of reference is television with snappy dialogue,” who are bound to miss great films in an oversaturated movie market. No wonder he hated Joss Whedon movies. Based on the Minecraft-induced mini-riots, younger generations perceive movie theaters less as sacred venues to partake in art and more as Chuck E. Cheeses with big screens.

The Greats Eventually Chase Trends Too

Sadly, most of the trends that the two highlighted in their hour-long jeremiad haven’t been redressed; they’ve only festered and solidified as the film industry has lost relevance. However, neither Coppola nor Scorsese is immune to these tendencies. The irony is that both have spent extravagantly on their recent films, contradicting their own statements that “wildly out-of-control budgets” are irresponsible and self-indulgent. Scorsese’s Irishman was a costly misfire for Netflix.

Unfortunately for Coppola, he depleted his own life savings on his own CGI-laden bomb, unable to convince major studios to fund his dream project. Perhaps the film’s failure wasn’t so shocking after all. Coppola wisely explained all the way back in 1997 that CGI can overpower a director’s vision, empowering a director at the cost of flattening cinematography and flooding a tight script with rampant feature creep. In other words, Megalopolis. Money isn’t always the solution. Sometimes it is yet another problem. That’s the ultimate takeaway. Today, the “independent movement” Scorsese spoke of as the “lifeblood” of future filmmaking isn’t short films on grainy 16mm, but places like YouTube, where Bo Burnham got his start. Close enough. The two masters might have got some minor details wrong, but the pair were otherwise depressingly accurate.