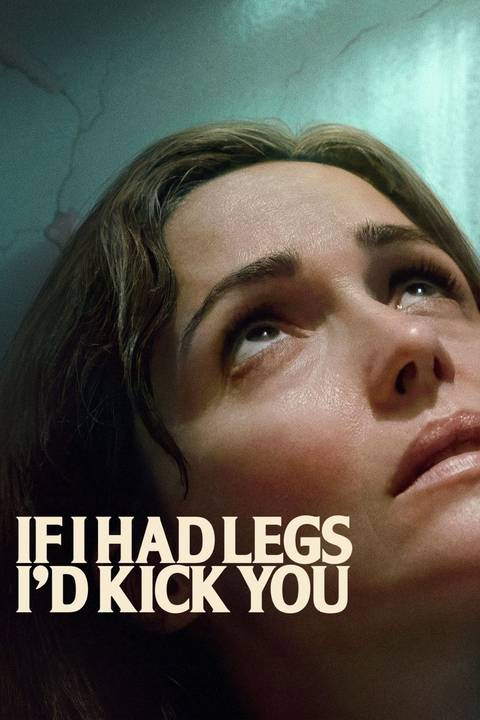

17 years after making her feature directing debut with Yeast (starring future filmmaking legend Greta Gerwig, no less), Mary Bronstein returns with her long-awaited follow-up, If I Had Legs I’d Kick You. With a god-level performance from Rose Byrne and impressive supporting turns from Conan O’Brien and A$AP Rocky, Bronstein’s second feature – an instant classic in the “woman on the verge” genre – was more than worth the wait. Bronstein delivered one of the best films of 2025, an intensely relatable and darkly comedic psychodrama that’s riveting from start to finish.

Ahead of its expansion to theaters nationwide this weekend, I spoke with Bronstein about her hiatus from filmmaking, how she managed to book Conan O’Brien for a legit acting gig, and why everyone can relate to Rose Byrne losing her f**king mind.

From the moment Rose Byrne shoved a bunch of pizza cheese in her mouth, I knew this movie was for me.

Mary Bronstein: I love that.

It’s been 17 years since your directorial debut, Yeast. What took so long?

Bronstein: I premiered Yeast in Austin at SXSW in competition, when the wonderful Matt Dentler was the programmer, and he made space for movies like mine to play at a festival like that, which now wouldn’t happen. But people were not ready for that movie. I had a bad experience with how people talked to me about the movie. It was a very male-dominated time for filmmaking and film festivals. It’s male-dominated now. It’s always been male-dominated, and in the independent space it was very male-dominated. And I had an experience with that film where I felt like I didn’t understand where there was room for me. I didn’t understand what the hostility was about [Yeast], a hostility that made me feel like, oh, there’s no room for me to make movies.

Where do you think that hostility came from?

Bronstein: The hostility was that it was a radically female film [that was] made, written and directed by a woman who has no interest in and doesn’t give a s**t who likes it or doesn’t like it. And so I did something which I don’t regret, because I think it made me able to make the work I’m making now. I stepped out. I said, well, maybe there’s no room for me. I went to graduate school. I got a degree in psychology. I worked in the New York City public hospital system doing play therapy with children in hospitals. Then I had a child. I did academic writing, like original feminist theory writing. And then I came to a place where my daughter got ill, and I had an existential crisis. I put everything into taking care of her, and I feel myself disappearing, but she’s going to get better, and then what?

I just came back to myself and said, “Well, what is the core of me?” I’m an artist, I’m a filmmaker, I’m a writer, I make films. That’s my form, and I started writing this film, and that’s what happened. It’s a longer time than I would have wanted it to be, but it was the right time.

I have a theory that if you try to make something for everyone, you’re making something for nobody.

And by the way, now people are ready for Yeast. It screens constantly in theaters around the country and in other countries too. It was on [the Criterion Channel]. I don’t think the female thing has gotten better, but I think that people are angry now, and so they are ready for a film that, at the base of it, there’s a rage and aggression. That’s been a wonderful experience.

But what I wanted to say, too, is that in order to make a good movie, you have to have had had experiences with life. You have to have engaged with life. And there’s a thing that I call “making movies about movies,” which is somebody that has, you know, watched movies their whole life. They go to film school, they get out of film school, and they’re making movies. What are you making a movie about? You’re essentially making a movie about movies.

We’re in an era where a lot of our media is extremely referential.

Bronstein: That’s what I mean. And it’s sort of like, all I want is new ideas. All I want to watch is something that’s new and original. I’m 46 years old. I’ve been watching movies and television for that long, and I don’t need to see a film where it’s like, you’ve seen Kubrick’s work, I get it. I already saw it. I don’t need to see it in this movie. What’s your idea? And that’s kind of where I’m at as a viewer, and so, as an artist, that’s also where I’m at, where it’s like every movie that I’ve ever seen is inside my body. Yeah, sure, some of them come out in my work, but that’s a natural reference. The greatest pleasure would be if somebody came up to me and was like, “That scene kind of reminds me of this thing,” and then I’d be like, ah, yeah, that’s just a natural reference. You know, Orson Welles said [something] which I believe in. And he said this in the ’50s, when we hadn’t had that many decades of movies. He said the worst thing that’s happened to filmmaking is the homage.

There’s also a lack of perspective. And that’s something I think about a lot, especially with the proliferation of ChatGPT, which has no perspective.

Bronstein: It’s not alive. It doesn’t have a brain.

But your movie does have a very clear perspective, and I think it does a great job of hitting on something so specific, but pulling off the movie magic of making it so relatable to people who can’t identify with the situation. I’m not a mother, but I watched If I Had Legs I’d Kick You, and as someone with anxiety, it feels like watching the inside of my brain.

Bronstein: I have a theory that if you try to make something for everyone, you’re making something for nobody. It’s weird, because it’s counterintuitive, but the more specific a thing is, the more people can find themselves in it, because it’s something that never happened to you. So you have to find yourself in the feeling, and who hasn’t been overwhelmed in their life? Who hasn’t had a crisis happen in their life that makes them question their sanity? Who hasn’t been in a period of their life where they thought the whole universe was against them? Who hasn’t been that stressed out? And you just want someone to say, “Go take a day off. Go lie down.” I’ve gotten amazing reactions from people that don’t have children – from men, from young people, and from older people, and everybody in between. And it has delighted me because it’s so pure. You know, the main character is a mother and is dealing with a child, but also she’s dealing with a child in a situation that 99% of people with children will never deal with, which is a seriously ill child. So she’s not even having a typical experience of motherhood.

When Linda says, “This is not how it was supposed to be,” it feels so visceral.

Exactly, and that’s part of her thing. It’s not fair. This is not fair.

I’ve had many conversations with myself and with my own therapist, when I’m in a pattern of bad luck, where I wonder if there’s a sign on my forehead, or if the universe is conspiring against me. It’s always when everything feels the most unbearable. You are more exhausted than you think you can possibly be, and that’s when you get a flat tire. That’s when one little thing just pushes you over the edge.

Bronstein: And that’s what this movie is. That’s the energy of this movie. It’s sort of like when that’s happening, all the things equal out to the same amount of stress, even when they’re not. With the parking attendant, for example, [Linda] is as upset about that as she is about the child’s illness; as she is about the fact that the girl won’t sell her the f**king wine; as she is about the fact that her husband is at a baseball game. It’s all equal, but if you step back, it’s not all equal. The problem is your daughter. Forget about the parking attendant. But like you said, you can’t. It’s that thing where everything’s going wrong, and then your pencil breaks, and you lose your f**king mind and start screaming. And it’s not about the pencil.

And she can’t see it because she’s in it. I love how there’s an echo in her therapy sessions with her patients, and in her sessions with her own therapist, played by Conan O’Brien. He’s essentially saying to her what she would say to another patient, and she just doesn’t want to hear it. But she doesn’t connect the dots.

Bronstein: She doesn’t. The dialog is circular, it’s just like a spiral, as I visualize it. She will tell her patient the exact thing, like you said, that she found so offensive. And she’s not making that connection at all. It’s up to the viewer to make the connection, and I’m so happy that you did. But it’s also that thing of like, what’s the worst thing that you can say to someone who’s upset? Calm down. Don’t do that. Calm down. No, it’s not okay. “Just get a good night’s sleep,” you know? And then she turns around and sort of says the same thing to her patients. That’s what people do.

It’s that thing where everything’s going wrong, and then your pencil breaks, and you lose your f**king mind and start screaming. And it’s not about the pencil.

I have to ask you about casting Conan O’Brien, who is just so damn good in this.

Bronstein: Isn’t he amazing? He’s incredible.

Did you already know him? How did you manage to get him?

Bronstein: I didn’t know him before this happened, and I’m very delighted to say we’re now friends actually, which is wild, because I’ve been a fan of his since I was like, 14 years old, when he came out with his original show. I didn’t want the therapist to be like a traditional Judd Hirsch in a cardigan thing. That’s kind of always how therapists are. They are always wearing a cardigan and have a scruffy beard. I don’t want that. I’ve never had a therapist like that. I wanted something different, and the way that this story unfolds with the therapist, is not how I’ve ever seen therapy depicted in a film, which is on purpose.

Literally, I was listening to his podcast one night, and he was interviewing David Letterman, and they’re both two of the funniest men that had an impact on my sense of humor as a young person. They’re having a serious conversation, and their voices are so calming to me. These are two men that I’ve heard, you know, for 30 years. And then I was thinking, Conan’s voice is so calming to me because it’s so familiar to me. So there’s something there. I was thinking that he’d be so good. I think, he could do this. We sent the script to him, and I couldn’t believe it when he said yes, but he said to me, “I’ve never done this before. I don’t know if I can do it, but I want to try to do it.” And I said, “Well, let’s do it.” It was a swing in the dark, because, like he said, who knows if he could [do it]? But I somehow knew that he could, and he did. And I want people to know that it’s not some random stunt casting, like a cameo or something. He is a proper actor in this movie. He turns in a performance in this movie that is as good as anything. It’s really great or better.

Similarly impressive is the cinematography, the really close shots of Rose Byrne’s face.

Bronstein: Her face is incredible.

I love watching her shove food into her mouth. Watching her get stoned and dissociating, listening to music on her phone. Very relatable.

Bronstein: Like girl, get headphones. And I can’t, because I actually lost them while getting stoned.

Just trying to have, like, five minutes…

Bronstein: Five minutes to yourself, absolutely. You get it.

The other thing I find so fascinating, that I think works so well in service of telling the story, is the decision to not show us the face of Linda’s daughter. We just see brief glimpses of her hair or a shoulder.

Bronstein: From the get-go, one of the things that I wanted to do with this film conceptually, quite radically, is to be 100% in Linda’s point of view. So we are only experiencing what Linda’s experiencing. Whether what she’s experiencing is actual or not, we don’t know. It’s real to her because she’s experiencing it. We must accept it. We are never anywhere where she’s not. We’re not in a space she’s not in. We’re with her, up in her head, up in her face, as you say. With the daughter, my idea was that she can’t see her daughter as a human being, a child that she can get any joy from or have a relationship with at this moment, because she sees her daughter only as part of this grand scheme of the universe to destroy her. She can only see the daughter as an obligation, an annoyance, a thing that’s put upon her, something that’s victimizing her, that she’s disappearing into, that she’s martyring herself to, and she cannot see her. That’s figurative, and then I decided to make it literal, because if she can’t see her, we can’t see her.

The other separate reason is a more technical reason, which is that I have Linda doing things in the film that are not okay and are upsetting for somebody that has a child. If you introduce the face of a child right away, our sympathy goes to the child, because that’s how we’re wired as human beings, and I didn’t want that. I wanted the viewer to stay with Linda no matter what she’s doing. That’s a calculated [decision].

I wanted to ask you about the Uncut Gems comparisons, because I can see where the tones are similar, but this feels like a somewhat pointed comparison. With you being married to Ronald Bronstein, the co-writer and producer of that film, when you hear people say that If I Had Legs I’d Kick You is like Uncut Gems, how do you feel about it?

I mean, the movies have nothing to do with each other in any way, except that both of them make people feel stressed out. That’s the comparison to be drawn. Also, we’re with a character that makes decisions that aren’t so great. The main character is usually the protagonist, the hero of the movie, yeah? And what both of these movies do is subvert that, and they make people very anxious and stressed out. But, you know, Ronnie and I met while making Frownland. We have commonalities together as people, and so of course we have commonalities together as creatives. But other than that, you know, it’s a weird comparison. I think the comparison is the feeling. I feel fine about it, because I’m proud of that movie. I’m proud of Josh [Safdie] and Ronnie for that movie, but I think that there’s a lack of movies that center on a woman that [viewers] can compare it to, so I think that’s part of it too.

The movie I thought about while watching your film is We Need to Talk About Kevin.

Bronstein: Oh, yes!

And I thought about how radical that movie felt at the time, and how radical your movie feels, and how not much has changed in 14 years.

Bronstein: And it’s 2025, and [We Need To Talk About Kevin] is still radical. That scene where [Tilda Swinton] can’t stand the sound of [her baby] crying, and so she goes to the construction site. That’s that… yeah. That’s great, no one’s brought up that movie to me. I love that movie.

- Release Date

-

October 10, 2025

- Runtime

-

113 minutes

- Director

-

Mary Bronstein

- Writers

-

Mary Bronstein

- Producers

-

Josh Safdie, Ronald Bronstein, Ryan Zacarias, Sara Murphy, Eli Bush

-

-

-

Mary Bronstein

Dr. Spring

-