Some pretty hyperbolic things are being said about One Battle After Another, the tenth and latest film from director Paul Thomas Anderson, who is beloved by critics but perhaps less revered by general audiences. Anderson has struggled to fill theaters the way contemporaries like Christopher Nolan or Quentin Tarantino do, and he has yet to win an Oscar. As such, people might be tempted to take the effusive praise One Battle After Another is receiving with a grain of salt. Sure, it has a 98% Rotten Tomatoes score and has been all but anointed the film of our time, and sure, directors like Steven Spielberg and Martin Scorsese are gushing about it. To the average moviegoer, that doesn’t mean it’s any different or better than Anderson’s previous so-called masterpieces, right?

This time, it does. One Battle After Another deserves its flowers, and it’s doing a lot of things so very right to be getting so very many of them, including things Anderson has never really attempted before as a director. While his usual strengths are still on full display (inventive visual and sound design, performances that profoundly reflect upon the American experience), One Battle After Another is unusually accessible and entertaining for a PTA movie.

Save for a few necessary breathers, it’s essentially two hours and 40 minutes of sustained cinematic action centered around one of the world’s biggest movie stars. But, on top of all that bravura filmmaking, Anderson does something else exactly right that propels this unexpected crowdpleaser into generationally important masterpiece territory, and it’s something few, if any, other filmmakers have been able to do.

‘One Battle After Another’ Is Made by Gen X for Gen Z

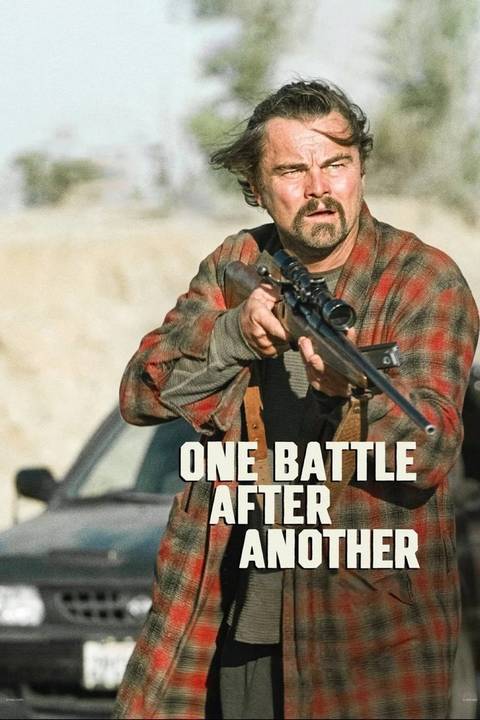

One Battle After Another is loosely inspired by Thomas Pynchon’s 1990 novel, Vineland, which looks back at the countercultural movements of the 1960s from the perspective of Reagan’s 1980s. Anderson’s film looks back at an alternate version of the late aughts from an alternate (but not unrecognizable) version of the present. In the first third of the movie, Leonardo DiCaprio’s Ghetto Pat and Teyana Taylor’s Perfidia Beverly Hills are busy freeing imprisoned migrants, fighting for abortion rights, and blowing up big banks while falling in love and evading the grasp of Sean Penn’s Col. Steven J. Lockjaw. 16 years later, Pat and his daughter (Chase Infiniti) — hiding out under the fake names Bob and Willa Ferguson — are suddenly fighting for their own lives when Lockjaw reemerges and comes looking for them with the full force of an extralegal police state behind him.

The first hurdle Anderson clears is his handling of the film’s potentially dicey politics. Pat and Perfidia are violent leftist revolutionaries, and the film doesn’t justify their actions. But make no mistake… Lockjaw and his forces, the ruling party they represent, and the secret white supremacist society that’s pulling all the strings are the villains. One Battle After Another isn’t a “both sides” movie. There’s no false equivalency between the French 75 and the Christmas Adventurers Club. The audience is meant to root for Benicio del Toro’s Sensei Sergio and his Underground Railroad for refugees, and it’s meant to root against Lockjaw when, for example, he sends a trooper in street clothes to throw a Molotov cocktail as justification to fire on civilians.

For all its grand set pieces and lofty ideas, of which there are many, One Battle After Another is primarily a story about a parent/child relationship set against a deeply flawed world. There, too, Anderson is able to achieve something authentic (it probably helps that he has four biracial and roughly teenage children with his longtime partner, Maya Rudolph). Willa loves her dad but is disappointed by him. She’s annoyed that he’s overprotective and paranoid, and almost always high or drunk. Bob wants to get her friends’ pronouns right, but can’t keep himself from calling them “homey” or threatening them like a regressive girl dad would.

Bob, just being himself, is the best joke in One Battle After Another. A lesser movie would’ve also made a joke of the non-binary kid or Willa’s attitude. Anderson never does. Just as he doesn’t both-sides the film’s politics, he refrains from both-sidesing the two distinct generations depicted in the story. From the anarchists to the fascists, it’s Gen X and the Boomers that are made to be ridiculous and hypocritical… no one more so than Penn’s tragically insecure bigot in fatigues. Willa’s generation is never mocked. Movies that cover similar ground, like this year’s Eddington, may have their points, but they often feel the need to portray Gen Z as ridiculous, hypocritical, and insufferable, which undermines any legitimate complaints and concerns young people might have about their future.

There’s More to the Multigenerational Story Than Meets the Eye

Anderson’s modern American epic is already quite complex on its surface, juggling its many characters, plot twists, and dissonant tones like grenades with their pins out, all while the camera hardly ever stops moving. It would still be a marvel if it were only about oppression and unrest, nativism and immigration, race and gender, and torn apart families. But the subtext in One Battle After Another is as deep as one of Daniel Plainview’s oil wells, and just as dark. It’s a film about one generation having failed another… and another, and another, stretching all the way back to the founding of what we call America.

In the text of the film, Willa’s parents have failed her twice; they failed to defeat authoritarianism in their 20s, and they failed her as parents in their 30s and 40s. Subtextually, it’s as if the filmmakers are earnestly apologizing to today’s youth for the world that’s being left to them, and just as earnestly hoping they can do better. The people who hold power in society (especially rich white men in their 50s and 60s, as Anderson, DiCaprio, and Penn are) are rarely humble enough to admit they didn’t live up to their ideals. For anyone who wants to read as much into it, Anderson has planted a damning truth bomb to that effect, right in the heart of the film’s demented love triangle.

There’s plenty to pick apart about the extremely charged entanglement between Perfidia and Lockjaw. The power dynamics alone warrant a dissertation. But let’s take the film’s climactic reveal about Willa’s parentage as an allegory. Willa clearly represents America and its future. As it turns out, she was not born of love to a well-intended, progressive father stumbling, however stoned, toward justice. She’s born of hate and subjugation to a bitter, mediocre father stumbling ragefully toward his, hers, and everyone else’s demise. At a time in which museums are being pressured to sanitize the country’s past, it’s bold to suggest, even symbolically, that America has been broken since its birth, because of its birth.

One Battle After Another may have been made by a bunch of Gen X guys, but it plays like the first movie of a new era. Anderson was able to capture the frustration and disillusion that so many millennials and Gen Z-ers feel when the America of myth doesn’t match the America they actually live in. And just like Bob can’t fix everything for Willa, Paul Thomas Anderson can’t fix everything with a movie, but he can at least let us know that he gets it. And that’s a start. One Battle After Another is in theaters now.

- Release Date

-

September 26, 2025

- Runtime

-

162 minutes